Go Basics: A Beginner's Guide to Golang

What is Golang?

- Go is a cross-platform, open source programming language

- Go can be used to create high-performance applications

- Go is a fast, statically typed, compiled language known for its simplicity and efficiency

- Go was developed at Google by Robert Griesemer, Rob Pike, and Ken Thompson in 2007

What is Go used for?

- Web development (server-side)

- Developing network-based programs

- Developing cross-platform enterprise applications

- Cloud-native development

Why use Go?

- Go is fun and easy to learn

- Go has fast run time and compilation time

- Go supports concurrency

- Go has memory management

- Go works on different platforms (Windows, Mac, Linux, Raspberry Pi, etc.)

Note For Golang

- Statically typed - Types are checked at compile time

- Compiled Language - Source code is compiled into machine code

- Fast run time - Fast execution time

- Fast compile time - Fast compilation

- Has automatic garbage collection

- Does not support classes and objects

- Does not support inheritance

Go Syntax

A Go program consists of the following parts:

- Package declaration

- Import packages

- Functions

- Statements and expressions

package main // every program is part of a package

import "fmt" // import is used to include other packages

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello World!")

}

Go Variables

Go has several basic data types:

int- stores integers (whole numbers), such as 123 or -123float32- stores floating point numbers, such as 19.99 or -19.99string- stores text, such as "Hello World"bool- stores values with two states: true or false

Declaring Variables

In Go, there are two ways to declare a variable:

1. With var keyword

var variablename type = value

// Example

var name string = "John"

var age int = 25

Note: You must specify either type or value (or both).

2. With := sign (Short Declaration)

variablename := value

// Example

name := "John"

age := 25

Note: The compiler determines the type based on the assigned value. You cannot declare a variable using

:=without assigning a value. If a variable is declared but not used, a compile-time error will occur.

Declare Multiple Variables

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// With type - can only declare one type per line

var a, b int = 1, 3

fmt.Println(a) // 1

fmt.Println(b) // 3

}

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Without type - can declare different types on the same line

var a, b = 6, "Hello"

fmt.Println(a) // 6

fmt.Println(b) // Hello

}

Naming Rules

- A variable name must start with a letter or an underscore character (

_) - A variable name cannot start with a digit

- A variable name can only contain alpha-numeric characters and underscores (

a-z,A-Z,0-9, and_) - Variable names are case-sensitive (

age,AgeandAGEare three different variables) - There is no limit on the length of the variable name

- A variable name cannot contain spaces

- The variable name cannot be any Go keywords

Go Constants

const CONSTNAME type = value // unchangeable read-only value

Note: When declaring a constant, the value must be assigned immediately.

Constants Types

- Typed constants

- Untyped constants

const A int = 1 // Typed constant

const A = 1 // Untyped - compiler automatically determines type based on value

Printf Function

The Printf() function first formats its argument based on the given formatting verb and then prints them.

Common formatting verbs:

| Verb | Description |

|---|---|

%v | Prints the value in the default format |

%#v | Prints the value in Go-syntax format |

%T | Prints the type of the value |

%% | Prints the % sign |

var i string = "Hello"

fmt.Printf("i has value: %v and type: %T\n", i, i)

// Output: i has value: Hello and type: string

Integer Types

Go supports both signed and unsigned integers:

var x int = 500 // Signed integer (can be positive or negative)

var y int = -4500 // Negative signed integer

var z uint = 43 // Unsigned integer (only positive)

Go Arrays

Arrays have a fixed length and store elements of the same type.

Declaring Arrays

1. With var keyword

var array_name = [length]datatype{values} // length is defined

var array_name = [...]datatype{values} // length is inferred

2. With := sign

array_name := [length]datatype{values} // length is defined

array_name := [...]datatype{values} // length is inferred

Example

// Defined Length

var arr1 = [3]int{1, 2, 3}

arr2 := [5]int{4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

// Inferred Length

var arr3 = [...]int{1, 2, 3}

arr4 := [...]int{4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

Array Initialization

If an array or one of its elements has not been initialized, it gets the default value.

Note: The default value for

intis0, and the default value forstringis"".

arr1 := [5]int{} // not initialized

arr2 := [5]int{1, 2} // partially initialized

str1 := [5]string{} // not initialized

fmt.Println(arr1) // [0 0 0 0 0]

fmt.Println(arr2) // [1 2 0 0 0]

fmt.Println(str1) // [ ]

Initialize Specific Elements

arr1 := [5]int{1:10, 2:40}

fmt.Println(arr1) // [0 10 40 0 0]

Find Length of an Array

arr1 := [4]string{"Volvo", "BMW", "Ford", "Mazda"}

arr2 := [...]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

fmt.Println(len(arr1)) // 4

fmt.Println(len(arr2)) // 6

Go Slices

Slices are similar to arrays, but are more powerful and flexible. Unlike arrays, the length of a slice can grow and shrink as you see fit.

Creating Slices

There are several ways to create a slice:

1. Using []datatype{values} format

slice_name := []datatype{values}

2. Create a slice from an array

var myarray = [length]datatype{values}

myslice := myarray[start:end] // start is inclusive, end is exclusive

3. Using the make() function

slice_name := make([]type, length, capacity)

Note: If the capacity parameter is not defined, it will be equal to length.

Length and Capacity

len()- returns the length of the slice (number of elements)cap()- returns the capacity of the slice (number of elements the slice can grow to)

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

myslice1 := []int{}

fmt.Println(len(myslice1)) // 0

fmt.Println(cap(myslice1)) // 0

fmt.Println(myslice1) // []

myslice2 := []string{"Go", "Slices", "Are", "Powerful"}

fmt.Println(len(myslice2)) // 4

fmt.Println(cap(myslice2)) // 4

fmt.Println(myslice2) // [Go Slices Are Powerful]

}

Using make() Function

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

myslice1 := make([]int, 5, 10)

fmt.Printf("myslice1 = %v\n", myslice1) // [0 0 0 0 0]

fmt.Printf("length = %d\n", len(myslice1)) // 5

fmt.Printf("capacity = %d\n", cap(myslice1)) // 10

// Without capacity parameter

myslice2 := make([]int, 5)

fmt.Printf("myslice2 = %v\n", myslice2) // [0 0 0 0 0]

fmt.Printf("length = %d\n", len(myslice2)) // 5

fmt.Printf("capacity = %d\n", cap(myslice2)) // 5

}

Multidimensional Slices

board := [][]string{

{"_", "_", "_"},

{"_", "_", "_"},

{"_", "_", "_"},

}

// The first [] is the row number and the second [] is the column number

board[0][0] = "X"

board[2][2] = "O"

board[1][0] = "Z"

board[1][2] = "Z"

fmt.Println(board) // [[X _ _] [Z _ Z] [_ _ O]]

Modify Slices

Access Elements

prices := []int{10, 20, 30}

fmt.Println(prices[0]) // 10

fmt.Println(prices[2]) // 30

Change Elements

prices := []int{10, 20, 30}

prices[2] = 50

fmt.Println(prices[2]) // 50

Append Elements

slice_name = append(slice_name, element1, element2, ...)

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

myslice1 := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

fmt.Printf("myslice1 = %v\n", myslice1) // [1 2 3 4 5 6]

fmt.Printf("length = %d\n", len(myslice1)) // 6

fmt.Printf("capacity = %d\n", cap(myslice1)) // 6

myslice1 = append(myslice1, 20, 21)

fmt.Printf("myslice1 = %v\n", myslice1) // [1 2 3 4 5 6 20 21]

fmt.Printf("length = %d\n", len(myslice1)) // 8

fmt.Printf("capacity = %d\n", cap(myslice1)) // 12

}

Append One Slice to Another

slice3 = append(slice1, slice2...)

Note: The

...after slice2 is required.

Go Conditions

If Statement

if 20 > 18 {

fmt.Println("20 is greater than 18")

}

If-Else Statement

if condition {

// code to be executed if condition is true

} else {

// code to be executed if condition is false

}

Else-If Statement

if condition1 {

// code to be executed if condition1 is true

} else if condition2 {

// code to be executed if condition1 is false and condition2 is true

} else {

// code to be executed if condition1 and condition2 are both false

}

Go Switch

The switch statement is used to select one of many code blocks to execute.

Note: Unlike C, C++, Java, and JavaScript, Go's switch only runs the matched case, so it does not need a

breakstatement.

Single Case

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

day := 3

switch day {

case 1:

fmt.Println("Monday")

case 2:

fmt.Println("Tuesday")

case 3:

fmt.Println("Wednesday")

case 4:

fmt.Println("Thursday")

...

default:

fmt.Println("Invalid day number")

}

}

Multi Case

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

day := 5

switch day {

case 1, 3, 5:

fmt.Println("Odd weekday")

case 2, 4:

fmt.Println("Even weekday")

case 6, 7:

fmt.Println("Weekend")

default:

fmt.Println("Invalid day number")

}

}

Go Loops

The for loop is the only loop available in Go.

Basic For Loop

for statement1; statement2; statement3 {

// code to be executed for each iteration

}

statement1- Initializes the loop counter valuestatement2- Evaluated for each iteration. If TRUE, the loop continues. If FALSE, the loop ends.statement3- Increases the loop counter value

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

fmt.Println(i)

}

}

// Output: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

Continue Statement

The continue statement is used to skip one or more iterations and continue with the next iteration.

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

if i == 3 {

continue

}

fmt.Println(i)

}

// Output: 0, 1, 2, 4

Break Statement

The break statement is used to stop the loop execution.

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

if i == 3 {

break

}

fmt.Println(i)

}

// Output: 0, 1, 2

Range Keyword

The range keyword is used to iterate through arrays, slices, or maps. It returns both the index and the value.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fruits := [3]string{"apple", "orange", "banana"}

for idx, val := range fruits {

fmt.Printf("%v\t%v\n", idx, val)

}

}

// Output:

// 0 apple

// 1 orange

// 2 banana

Note You can use the

_underscore symbol to ignore either idx or value.

Go Structs

A struct is used to collect members of different data types into a single variable.

type Person struct {

name string

age int

job string

salary int

}

func main() {

var pers1 Person

pers1.name = "Hege"

pers1.age = 45

pers1.job = "Teacher"

pers1.salary = 6000

fmt.Println("Name:", pers1.name)

fmt.Println("Age:", pers1.age)

fmt.Println("Job:", pers1.job)

fmt.Println("Salary:", pers1.salary)

}

Go Maps

- Maps store data values in key:value pairs

- Each element in a map is a key:value pair

- A map is an unordered and changeable collection that does not allow duplicates

- The default value of a map is

nil

Creating Maps

var a = map[KeyType]ValueType{key1:value1, key2:value2, ...}

b := map[KeyType]ValueType{key1:value1, key2:value2, ...}

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var a = map[string]string{"brand": "Ford", "model": "Mustang", "year": "1964"}

b := map[string]int{"Oslo": 1, "Bergen": 2, "Trondheim": 3}

fmt.Printf("a\t%v\n", a)

fmt.Printf("b\t%v\n", b)

}

Creating Maps with make Function

var a = make(map[KeyType]ValueType)

b := make(map[KeyType]ValueType)

var a = make(map[string]string)

a["brand"] = "Ford"

b := make(map[string]int)

b["Oslo"] = 1

Warning: The

make()function is the best (most correct) way to create an empty map. If you create an empty map differently and write to it, it will cause a runtime panic.

Check If Key Exists

val, ok := map_name[key]

var a = map[string]string{"brand": "Ford", "model": "Mustang"}

val1, ok1 := a["brand"] // Checking for existing key

val2, ok2 := a["color"] // Checking for non-existing key

fmt.Println(val1, ok1) // Ford true

fmt.Println(val2, ok2) // false

Maps are Reference Types in Go

Key point: If two map variables refer to the same Hash Table (memory location), changing one will automatically change the other.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

a := map[string]string{

"brand": "Ford",

"model": "Mustang",

"year": "1964",

}

b := a // b references the same map as a

fmt.Println(a)

fmt.Println(b)

b["year"] = "1970"

fmt.Println("After change to b:")

fmt.Println(a)

fmt.Println(b)

}

// Output:

// map[brand:Ford model:Mustang year:1964]

// map[brand:Ford model:Mustang year:1964]

// After change to b:

// map[brand:Ford model:Mustang year:1970]

// map[brand:Ford model:Mustang year:1970]

Go Pointers

A pointer is a variable that stores the Memory Address of another variable, rather than storing the value directly.

Without Pointer

x := 10

y := x // y is a copy of x

y = 20

fmt.Println("x:", x) // 10 - unchanged

fmt.Println("y:", y) // 20

With Pointer

x := 10

p := &x // p points to x

*p = 20 // change the value at the address p points to

fmt.Println("x:", x) // 20 - changed!

&x- gives you the memory address ofx(pointer)p := &x-pis a pointer tox*p- "go to the memory address that p points to"*p = 20- "change the value at that address to 20"

Using Pointers in Functions

func addOne(n *int) {

*n = *n + 1

}

func main() {

x := 5

addOne(&x)

fmt.Println("x after addOne:", x) // 6

}

Receiver Functions

Receiver functions allow custom types (structs) to use dot (.) notation like methods. Similar to class methods in other languages, Go also allows structs and methods to be used together.

1. Pointer Receiver

Pointer Receiver can operate on the existing structure without copying the entire struct. Therefore, it can directly modify values in the original struct. The advantage is that it can work on the existing struct without copying, saving memory.

type Coordinate struct {

X int

Y int

}

func (coord *Coordinate) shiftBy(x, y int) {

coord.X += x

coord.Y += y

}

func main() {

coord := Coordinate{10, 10}

coord.shiftBy(1, 1) // modify with dot notation

}

2. Value Receiver

Value Receiver copies the original struct and operates on that copy, so you don't have to worry about accidentally modifying the original data incorrectly. It becomes more immutable logic.

package main

type Coordinate struct {

X int

Y int

}

func (c Coordinate) shiftBy(other Coordinate) Coordinate {

return Coordinate{other.X - c.X, other.Y - c.Y}

}

func main() {

coord1 := Coordinate{2, 2}

coord2 := Coordinate{1, 5}

shiftedCoord := coord1.shiftBy(coord2)

println("Shifted Coordinate:", shiftedCoord.X, shiftedCoord.Y) // (-1, 3)

}

Recap

- Receiver functions are commonly used when creating clean and convenient APIs

- I use Pointer Receiver more often. I don't use Value Receiver very much.

Iota

The iota keyword is used to automatically assign values to constants.

- Auto increment:

iotaincrements by 1 for each constant - Zero-based: Starts at 0 for the first constant

- Reset: Resets to 0 at the beginning of each new

constblock

const (

A = iota // A = 0

B // B = 1

C // C = 2

D // D = 3

)

Skipping Values (Using underscore)

const (

A = iota // A = 0

_ // 1 (skipped)

_ // 2 (skipped)

D // D = 3

)

Variadics

Variadic functions can accept an unlimited number of parameters.

func sum(nums ...int) int { // variadic parameter is a slice

result := 0

for _, num := range nums {

result += num

}

return result

}

func main() {

a := []int{1, 2, 3}

b := []int{4, 5, 6}

all := append(a, b...)

answer := sum(all...)

fmt.Println("The sum of all numbers is:", answer) // 21

}

Init Functions

The init() function is used for initialization steps and runs before the main() function.

Usage When you need to check network connections, perform some validations in advance, or for expensive operations like DB connections and cache.

var EmailExpr *regexp.Regexp

func init() {

compiled, err := regexp.Compile(`.+@.+\..+`)

if err != nil {

panic("failed to compile email regex")

}

EmailExpr = compiled

fmt.Println("Email regex compiled successfully")

}

Error Handling

- Errors are returned as the last return value from a function

errors.New()is used to create simple errors- Always check

if err != nilfor functions that return errors

type error interface {

Error() string

}

Readers and Writers(Go I/O)

Readers and Writers are fundamental interfaces for reading from and writing to I/O sources.

Readers are low-level implementations, and usually the bufio package is used to reduce buffer management overhead.

Reader Interface

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

The

Read()function fills the provided buffer p and returns n → the number of bytes that can be read. When all bytes have been read, err == io.EOF. EOF means End of line.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"io"

"strings"

)

func main() {

reader := strings.NewReader("SAMPLE")

var newString strings.Builder

buffer := make([]byte, 4)

for {

n, err := reader.Read(buffer)

chunk := buffer[:n]

newString.Write(chunk)

fmt.Printf("Read %v bytes %q\n", n, chunk)

if err == io.EOF {

break

}

}

fmt.Printf("Final string: %q\n", newString.String())

}

// Output:

// Read 4 bytes "SAMP"

// Read 2 bytes "LE"

// Read 0 bytes ""

// Final string: "SAMPLE"

bufio package

The bufio package provides Read & Write buffering processes so you don't need to manually manage buffers or construct data, using functions like ReadString('\n').

package main

import (

"bufio"

"fmt"

"io"

"strings"

)

func main() {

reader := strings.NewReader("SAMPLE")

buffered := bufio.NewReader(reader)

text, err := buffered.ReadString('\n')

if err == io.EOF {

fmt.Println(text)

} else {

fmt.Println("Something went wrong")

}

}

Writer Interface

The Writer interface is symmetric to Reader.

package main

import (

"bytes"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

buffer := bytes.NewBufferString("")

n, err := buffer.WriteString("SAMPLE")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

} else {

fmt.Printf("Wrote %v bytes: %q\n", n, buffer)

}

}

Type Embedding

Go doesn't have Class Inheritance like other languages, but similar functionality can be achieved through Embedding.

1. Embedding Interfaces

Embedding interfaces can be built by including other interfaces within one interface.

Advantage: You don't need to write duplicate code and can organize large interfaces into smaller parts. This also makes codebases much easier to maintain.

package main

import "fmt"

type Whisperer interface {

Whisper() string

}

type Yeller interface {

Yell() string

}

type Embedded interface {

Whisperer

Yeller

}

func Talk(e Embedded) {

fmt.Println(e.Whisper())

fmt.Println(e.Yell())

}

2. Embedding Structs

Similarly, Embedding structs can be built by including other structs within one struct.

Embedding Structs have a special feature called field & method promotion, which allows direct access at the top-level struct without extra indirection.

package main

import "fmt"

type Account struct {

AccountId int

Balance int

Name string

}

type AccountManager struct {

Account

}

func main() {

account := AccountManager{Account{2, 1000, "John"}}

fmt.Println("Account:", account)

// No need to extra indirection `account.Account.Name`

fmt.Println("Name via embedded struct:", account.Name) // (field promotion)

}

Generics

Generics allow one function to handle multiple data types and also reduce code duplication. constraints interfaces can be used to define Generics.

func IsEqual[T comparable](a, b T) bool { // comparable is constraints

return a == b

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(IsEqual(2, 2)) // true

fmt.Println(IsEqual("far", "boo")) // false

fmt.Println(IsEqual('a', 'b')) // false

fmt.Println(IsEqual[uint8](4, 4)) // true

}

Creating Constraints

type Integer32 interface {

int32 | uint32

}

func SumNumbers[T Integer32](arr []T) T { // Integer32 is constraints

var sum T

for i := 0; i < len(arr); i++ {

sum += arr[i]

}

return sum

}

Note: When working with Generic constraints, types must match exactly. Sometimes when using Generics, types don't match and compile errors occur. In such cases, using

~calledgeneric approximationoften helps.

Function Literals

- Function literals (closures/anonymous functions) allow defining a function within a function.

- Function literals can be assigned to variables.

- Function literals can be passed as parameters to functions.

func helloWorld() {

fmt.Println("Hello,")

world := func() { // anonymous function

fmt.Println("World!")

}

world()

}

Closure

A closure is when a function can remember and use a variable from its outer scope.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

discount := 0.0 // value outside anonymous function (outer scope)

calcDiscount := func(subTotal float64) float64 {

if subTotal > 100 {

discount += 0.1

}

if subTotal > 300 {

discount += 0.3

}

return discount

}

fmt.Println(calcDiscount(50)) // 0

fmt.Println(calcDiscount(150)) // 0.1

fmt.Println(calcDiscount(400)) // 0.5

}

Defer

The defer keyword executes code after the function completes. Useful for cleanup operations.

Note: Multiple

deferstatements execute in LIFO (Last In, First Out) order.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Function beginning")

defer fmt.Println("one")

defer fmt.Println("two")

fmt.Println("Function End")

}

// Output:

// Function beginning

// Function End

// Two

// One

Concurrency

Concurrency is one of Go's most powerful features and what makes it stand out from other programming languages. This section covers everything about concurrent programming in Go.

What is Concurrency?

Normally, our code runs line by line sequentially. Concurrency is managing multiple pieces of code simultaneously, allowing them to work in turns.

Example - Think of a restaurant kitchen:

-

Without concurrency (Sequential): One chef does everything - cooks appetizer, waits for it to finish, then cooks main course, waits, then makes dessert. Customers wait a very long time!

-

With concurrency: The same chef works on 3 stoves simultaneously. While waiting for meat to cook, they chop vegetables; while waiting for vegetables to soften, they stir the soup. They're "handling" many tasks simultaneously.

-

Parallelism: Three chefs work on 3 stoves, each cooking simultaneously. This is when tasks are "actually working" simultaneously.

Two Types of Concurrent Code

| Type | Description | Real-Life Example |

|---|---|---|

| Asynchronous | Code can pause and resume; while paused, other code can run | One chef starts boiling water, then chops vegetables while waiting, does other needed tasks |

| Threaded (Parallel) | Runs truly simultaneously on multiple CPU cores | Multiple chefs cooking simultaneously |

Note: Go automatically chooses the best concurrency method based on the situation!

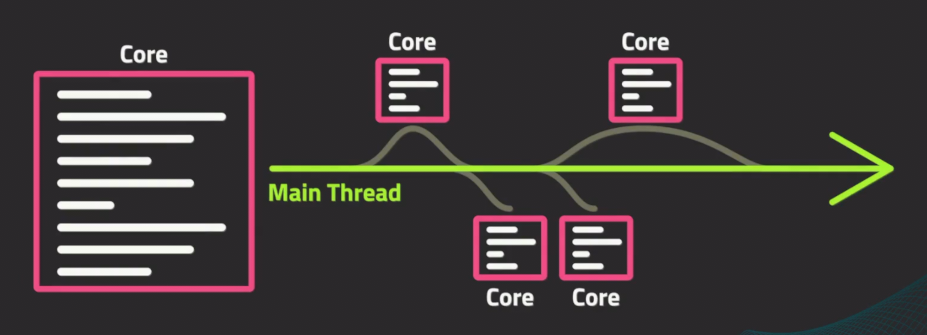

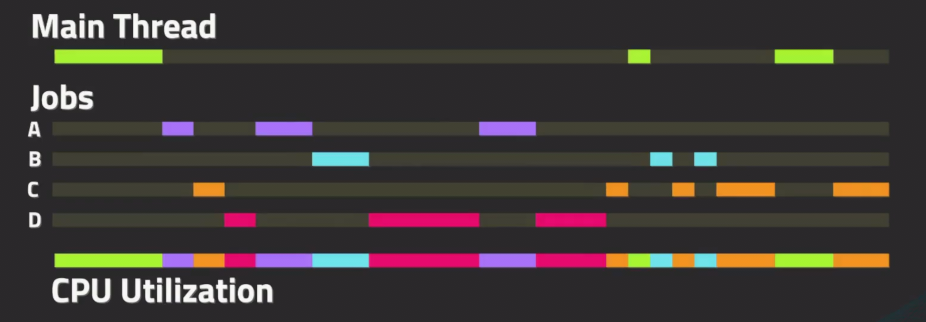

Thread Execution

Async Execution

Goroutines

Goroutines are Go's way of running functions concurrently. They are lightweight threads managed by Go runtime.

OS Threads typically use over 1MB of memory, but a Goroutine starts using only around 2KB. Therefore, a Go program can run tens of thousands of Goroutines simultaneously.

Example - You need to download 5 large files:

// Without Goroutines - downloads one at a time (SLOW!)

download("file1.zip") // Wait 10 seconds

download("file2.zip") // Wait 10 seconds

download("file3.zip") // Wait 10 seconds

// Total: 30+ seconds

// With Goroutines - downloads all at once (FAST!)

go download("file1.zip") // Start immediately

go download("file2.zip") // Start immediately

go download("file3.zip") // Start immediately

// Total: ~10 seconds (all download together)

Creating Goroutines

Simply add the go keyword before a function call.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func count(name string, amount int) {

for i := 1; i <= amount; i++ {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Printf("%s: %d\n", name, i)

}

}

func main() {

// Start goroutine - runs concurrently

go count("Goroutine", 5)

fmt.Println("Main: Waiting for goroutine...")

// Wait for goroutines to finish

time.Sleep(1000 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("Main: Program ended!")

}

Important: If the main function ends, all goroutines are terminated immediately! That's why we use

time.Sleepto wait for them. In real projects, instead oftime.Sleep, we use more systematic methods likechannelsorwait groupsbecause we don't know exactly how long the work will take.

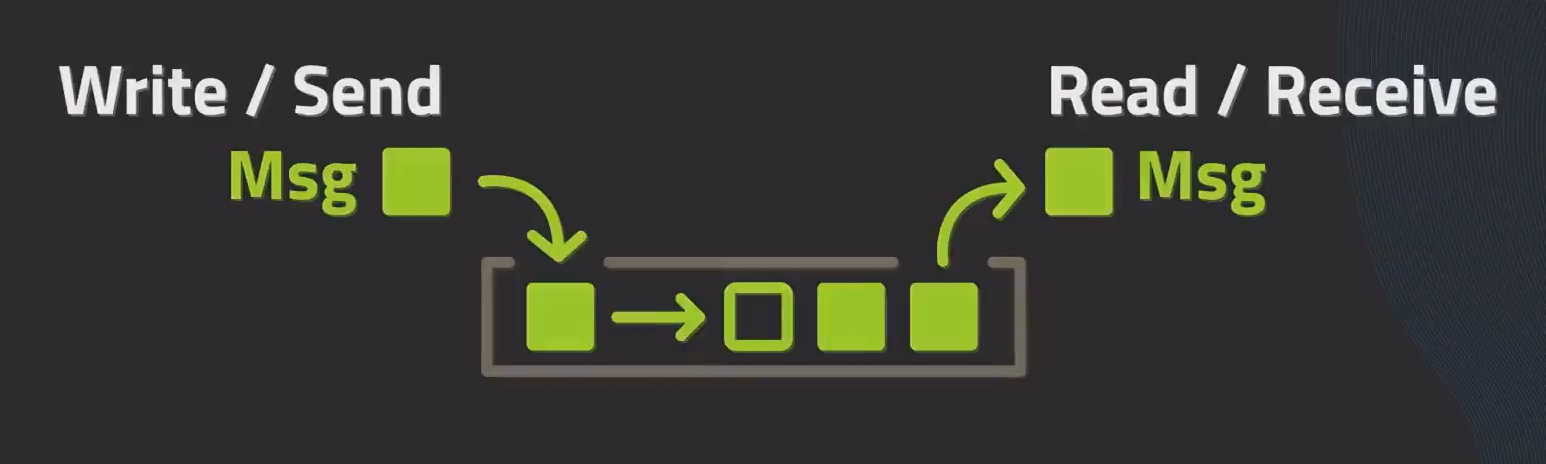

Channels

Channels are pipes that allow goroutines to communicate with each other safely. This implements Go's philosophy: "Don't communicate by sharing memory; share memory by communicating". Think of them as a way to send/receive messages (send/write end & receive/read end) between concurrent code.

Example - Think of a car factory assembly line:

- Station 1 builds the frame → sends to Channel → Station 2 receives

- Station 2 adds engine → sends to Channel → Station 3 receives

- Each station waits for data from the previous station via the channel.

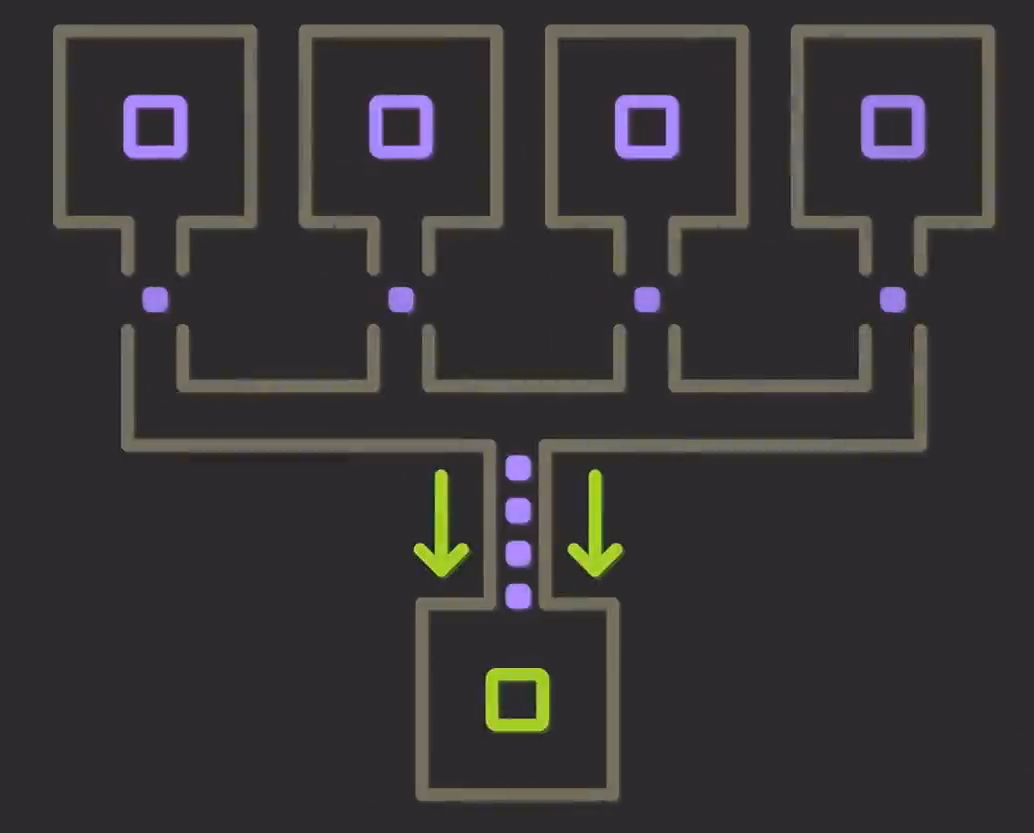

Channel Visual

Creating and Using Channels

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// creating a channel

messages := make(chan string)

go func() {

messages <- "Hello from goroutine!" // Sending to Channel

}()

msg := <-messages // Receiving from Channel

fmt.Println(msg) // Output: Hello from goroutine!

}

Channel Syntax

// Creating a channel

ch := make(chan int)

// Sending value to channel

ch <- 42

// Receiving value from channel

value := <-ch

Buffered and Unbuffered Channels

| Type | Behavior | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Unbuffered | Works only when Sender and Receiver are ready simultaneously (Synchronization) | When you want guaranteed delivery |

| Buffered | Can send data up to specified Capacity without blocking | For performance and batch work |

// Unbuffered channel - blocks before receive

// This means the Receiver must be present to send

unbuffered := make(chan int)

// Buffered channel - can hold 3 values before blocking

// The 4th will block the Sender

buffered := make(chan int, 3)

buffered <- 1 // Doesn't block

buffered <- 2 // Doesn't block

buffered <- 3 // Doesn't block

buffered <- 4 // BLOCKS! Buffer is full

Note: Messages in channels follow FIFO (First In, First Out) ordering.

Channel Selection

The select keyword lets you handle multiple channels simultaneously:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ch1 := make(chan string)

ch2 := make(chan string)

go func() {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

ch1 <- "Message from channel 1"

}()

go func() {

time.Sleep(200 * time.Millisecond)

ch2 <- "Message from channel 2"

}()

// Wait for messages from either channel

for i := 0; i < 2; i++ {

select {

case msg1 := <-ch1:

fmt.Println(msg1)

case msg2 := <-ch2:

fmt.Println(msg2)

}

}

}

Channels and Timeouts

Use time.After with select to implement timeouts:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ch := make(chan string)

go func() {

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second) // Simulate slow operation

ch <- "Result ready!"

}()

select {

case result := <-ch:

fmt.Println(result)

case <-time.After(1 * time.Second):

fmt.Println("Timeout! Operation took too long.")

}

}

// Output: Timeout! Operation took too long.

Synchronization

When multiple goroutines access Shared Data (a single variable) simultaneously, things can get messy and Race Conditions can cause unwanted problems. Synchronization helps prevent bugs and unpredictable behavior.

Example - Two people trying to withdraw money from the same bank account simultaneously:

- Account balance:

$100 - A wants to withdraw

$80 - B wants to withdraw

$50

Without synchronization:

- Both check balance:

$100✓ - Both withdraw their amounts

- Result:

-$30balance! 💥

With synchronization:

- A locks the account, checks

$100, withdraws$80, unlocks - B locks the account, checks

$20, insufficient funds ✓

Mutex (Mutual Exclusion)

Mutex provides a way to lock/unlock data so only one goroutine can access it at a time.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

type BankAccount struct {

balance int

mutex sync.Mutex

}

func (acc *BankAccount) Deposit(amount int) {

// Lock to prevent other goroutines from accessing

acc.mutex.Lock()

defer acc.mutex.Unlock() // Unlock when function ends

acc.balance += amount

fmt.Printf("Deposited %d, Balance: %d\n", amount, acc.balance)

}

func (acc *BankAccount) Withdraw(amount int) bool {

acc.mutex.Lock()

defer acc.mutex.Unlock()

if acc.balance >= amount {

acc.balance -= amount

fmt.Printf("Withdrew %d, Balance: %d\n", amount, acc.balance)

return true

}

fmt.Printf("Insufficient funds for %d, Balance: %d\n", amount, acc.balance)

return false

}

func main() {

account := &BankAccount{balance: 100}

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Simulate concurrent transactions

wg.Add(3)

go func() { defer wg.Done(); account.Deposit(50) }()

go func() { defer wg.Done(); account.Withdraw(80) }()

go func() { defer wg.Done(); account.Withdraw(50) }()

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Final Balance:", account.balance)

}

Why Use defer with Mutex?

Using defer ensures the mutex is always unlocked.

Without defer - Dangerous:

func (d *SyncData) Get(k string) int {

d.mutex.Lock()

if k == "" {

return 0 // ❌ Forgot to unlock! Mutex stays locked forever!

}

value := d.inner[k]

d.mutex.Unlock()

return value

}

With defer - Safe:

func (d *SyncData) Get(k string) int {

d.mutex.Lock()

defer d.mutex.Unlock() // ✅ Always unlocks, no matter how function ends

if k == "" {

return 0 // Unlock still happens!

}

return d.inner[k]

}

Wait Groups

Wait Groups let you wait for all goroutines to finish.

Example - Think of a team project where 5 people work on different parts:

- Assign tasks to everyone

- Wait for ALL team members to finish

- Only then can you submit the project

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"time"

)

func worker(id int, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

// Signal that one task is completed

defer wg.Done()

fmt.Printf("Worker %d starting\n", id)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(id) * 100 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Printf("Worker %d finished\n", id)

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

wg.Add(1) // Add one task to wait for

go worker(i, &wg)

}

// Wait until counter reaches zero (all work is done)

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("All workers completed!")

}

How it works:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

wg.Add(n) | Add n goroutines to wait for in the counter |

wg.Done() | Signal that one task is completed (decrement counter by 1) |

wg.Wait() | Block main until counter reaches 0 (all work is done). |

Concurrency Patterns

Concurrency patterns are standard solutions for common problems encountered when writing concurrent programming.

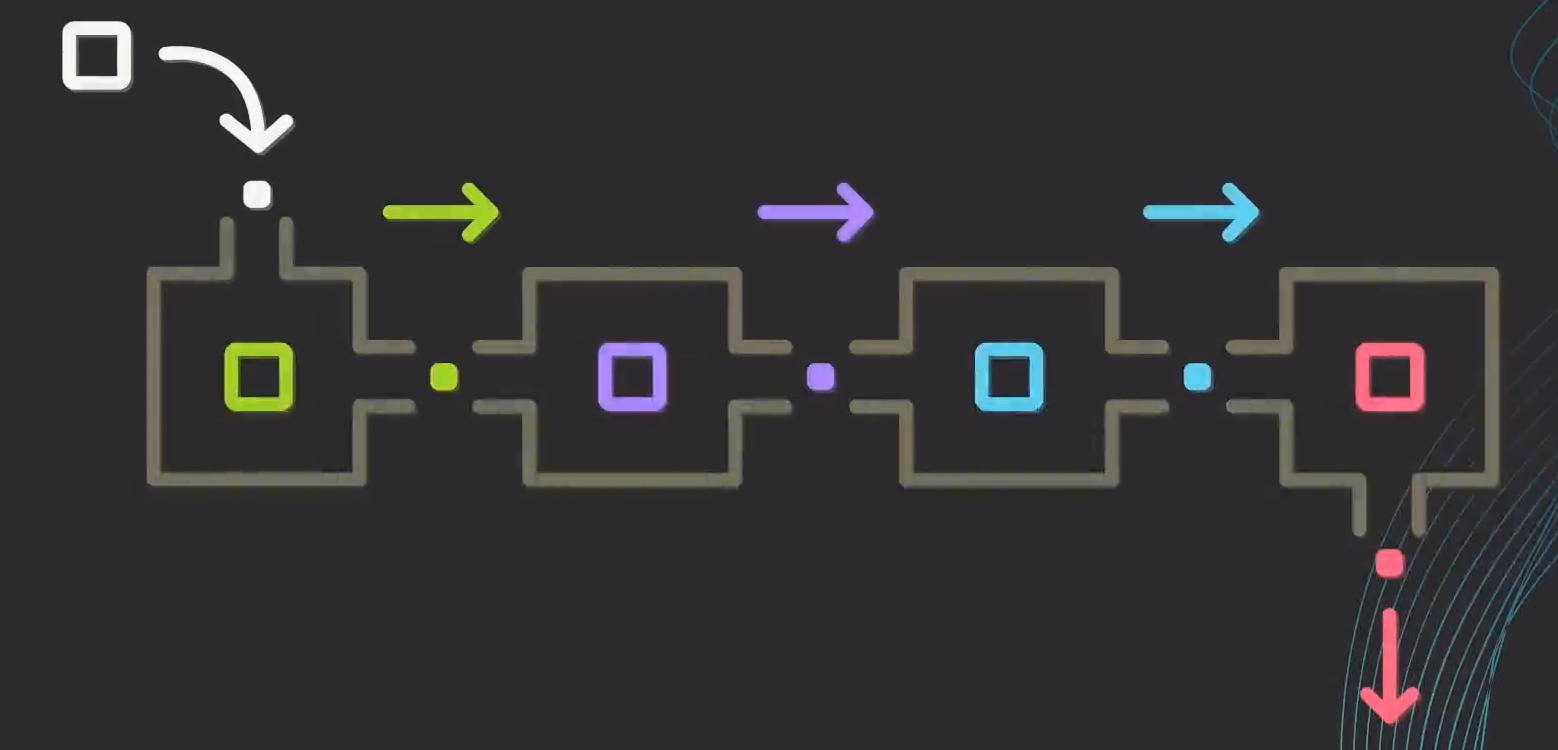

1. Pipeline Pattern

A system that processes data step by step. The output of one stage becomes the input for the next stage. Roughly speaking, there are three stages: Generator stage, Processing stage and Consumer stage.

Example - Food Processing Factory

[Raw Materials] → [Washing] → [Cutting] → [Cooking] → [Packaging] → [Shipping]

Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 Stage 5 Stage 6

Each stage:

- Receives input from previous stage

- Processes the data

- Sends output to next stage

Pipeline Visual

package main

import "fmt"

// Stage 1: Generator - produces numbers

func generator(nums ...int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

for _, n := range nums {

out <- n

}

close(out)

}()

return out

}

// Stage 2: Square - squares each number

func square(in <-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

for n := range in {

out <- n * n

}

close(out)

}()

return out

}

// Stage 3: Double - doubles each number

func double(in <-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

for n := range in {

out <- n * 2

}

close(out)

}()

return out

}

func main() {

// Connect pipeline: generator → square → double → print

nums := generator(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

squared := square(nums)

doubled := double(squared)

// Consume the final output

for result := range doubled {

fmt.Println(result)

}

}

// Output: 2, 8, 18, 32, 50

2. Fan-In Pattern

A pattern that collects data from multiple channels (Multiple Channels) and merges them into a single channel (Single Channel).

Example - Customer Service

Phone lines (channels) → One queue → Display showing all calls

Fan In

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func producer(name string, nums ...int) <-chan string {

out := make(chan string)

go func() {

for _, n := range nums {

out <- fmt.Sprintf("%s: %d", name, n)

}

close(out)

}()

return out

}

func fanIn(channels ...<-chan string) <-chan string {

out := make(chan string)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for _, ch := range channels {

wg.Add(1)

go func(c <-chan string) {

defer wg.Done()

for msg := range c {

out <- msg

}

}(ch)

}

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(out)

}()

return out

}

func main() {

ch1 := producer("Server-A", 1, 2, 3)

ch2 := producer("Server-B", 4, 5, 6)

ch3 := producer("Server-C", 7, 8, 9)

merged := fanIn(ch1, ch2, ch3)

for msg := range merged {

fmt.Println(msg)

}

}

3. Context for Cancellation

Context can be used to cancel all unfinished Goroutines simultaneously when needed.

Example - Search Engine

Search on multiple servers simultaneously, and when one server returns a result, cancel all other searches simultaneously.

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

func worker(ctx context.Context, name string) {

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

fmt.Printf("%s: Cancel signal received, stopping...\n", name)

return

default:

fmt.Printf("%s: Working...\n", name)

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

}

}

}

func main() {

// Create context with cancel function

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

// Start workers

go worker(ctx, "Worker-1")

go worker(ctx, "Worker-2")

go worker(ctx, "Worker-3")

// Let workers run for 2 seconds

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

// Cancel all workers

fmt.Println("\nMain: Cancelling all workers...")

cancel()

// Give workers time to clean up

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("Main: All done!")

}

4. Generator Pattern

Generators produce values only when needed, computing only when needed. The Generator pattern is excellent for Memory Efficiency. Instead of putting 1 million data points into an array and returning it, it produces one at a time when needed, which can significantly reduce memory usage.

Example - Streaming Service

Netflix doesn't download the entire movie at once. It generates/streams chunks while you watch.

package main

import "fmt"

// Generator: produces fibonacci numbers on demand

func fibonacci(n int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

a, b := 0, 1

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

out <- a

a, b = b, a+b

}

close(out)

}()

return out

}

func main() {

// Get first 10 fibonacci numbers

for num := range fibonacci(10) {

fmt.Println(num)

}

}

// Output: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34

Concurrency Best Practices

Do's ✅

- Use channels for communication between goroutines

- Use mutexes for shared state when channels don't fit

- Always close channels when done sending

- Use

deferfor unlocking mutexes - Use context for cancellation in long-running operations

- Use wait groups when you need to wait for multiple goroutines

Don'ts ❌

- Don't share memory without synchronization

- Don't create goroutines without termination logic (can cause Goroutine Leak)

- Don't forget that the main function ending kills all goroutines

- Don't lock a mutex twice without unlocking (causes deadlock)

- Don't send on a closed channel (causes panic)

Quick Reference

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Want to run code concurrently | go functionName() |

| Want to communicate between goroutines | Channels |

| Want to protect shared data | sync.Mutex |

| Want to wait for goroutines | sync.WaitGroup |

| Want to cancel operations | context.Context |

| Want to handle multiple channel operations | select |

| Want to timeout operations | time.After with select |

Go's concurrency model is excellent for building scalable, high-performance applications. Practice these patterns and you'll be writing professional Go code in no time!

"Generated by Nyein Phyo Aung"